Fabrics

This is the piece I read earlier tonight at the Istituto italiano di Cultura in Dublin, at the public event for the «Found in translation» course, run by Lia Miss and Catherine Dunne.

It is fiction based on the actual story.

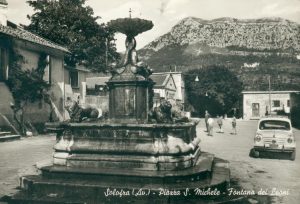

Solofra, Avellino, 1952.

«Girls, what are you doing? Go back to work!». Assuntinella swam across the world carrying her body as if it were a parcel: it bent down, it was the outcome of who knows what kind of serious illness. Nonetheless, she served for a long time as the commodore of a flotilla. Her troops were a group of twenty-ish sailor-tailor girls.

She pretended to be tough and stern. It was she, though, the one who used to jab her husband’s huge groin hernia with her favourite companion: a needle… And only to make the girls cackle.

Rosa used to work in Assuntinella’s dressmaker’s workshop.

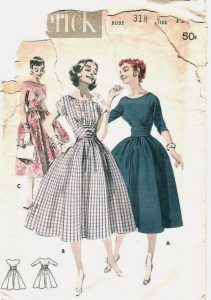

They handmade high fashion, haute couture.

They did not even dare to think of anything like this, though. Everyone simply thought of their job as their duty, their normal boring day-to-day life.

Moreover, they lived in a small village in the South of Italy.

It was soon after the Second World War: how could they have even thought of anything like «well, we are designers, we are protagonists of what is called “Made in Italy”»?

It was soon after the Second World War: how could they have even thought of anything like «well, we are designers, we are protagonists of what is called “Made in Italy”»?

All they knew was that they had to be as great as possible at what they did, since people paid them actual money, and trusted them. And money plus trust equals food and future.

Literally, people put themselves into their hands.

*

Via Mazzini, Verona, 2017

«Good morning».

«Good morning».

«Good morning. How can I help you?».

«Oh, I’m only taking a look, thank you. May I?».

«You’re more than welcome. Should you need anything, please, feel free to ask».

Two women against a black wall, silver letters: a «zed», an «a», an «r» and the final «a». «Zara», all together.

The one who has just come into the shop looks around slyly, holding on firmly to the Louis Vuitton bag she had finally been able to buy the day before: the one her friends had bought months ago. But now I’m there as well, at last.

The clerk wears a black trouser suit.

The last time she had had pasta was in 2012, she was fourteen.

*

Solofra, 1952.

«Girls, come here! What the hell are you doing at that window?»

«Girls, come here! What the hell are you doing at that window?»

They were looking at their sweethearts.

Each of the girls had a boyfriend.

Each of the boyfriends went in turn under the windows of the workshop, each of them whistling in a special way that was meant to be intended only for their girlfriend. Some drove a Vespa. Others were just walking.

The girls would pin their needles on the piece they were creating and rush to the window, one by one. As curious as little frantic monkeys, all of them giggling.

Boyfriends would throw little scraps of paper with love messages, a small stone wrapped in them. The girls, frenzied, would seize those gifts and read them silently.

«Rosa, let me see what Tonino wrote to you! Please!». My mother was kind of reluctant, but she gave them the love message, in the end. Since whenever you have the chance to make it clear to the world that someone loves you, there is no way to hide your pride…

*

Fabrics.

Textures.

Weight.

Fitting.

Balance.

Seams.

Brands.

Leather.

Tons of items, all the same, all the sizes, many colours.

*

Verona, 2017.

«Can I try this one on?».

«Can I try this one on?».

«Of course you can», says the Zara store clerk, the one with the black suit. «Which size would you like?». A quick look at the body. «Forty-two?», she asks. She knows it might be a generous evaluation.

«No, maybe a forty would do».

«Oh, perfect, then. I’ll go and get it for you. This is a wonderful dress. Good choice», the clerk says while picking the right size. «We sold dozens of these, in the past few weeks. Dozens. We had to ask Zara to have them sent again».

This words give the customer a thrill: and now, another box is going to be ticked, she thought.

*

Solofra, 1952.

«Girls! No more boyfriends now! Back to work!».

«Girls! No more boyfriends now! Back to work!».

A dress, a skirt, a pair of trousers, a shirt, a jacket: everything had to fall the proper way. And there was only one proper way: the right one. No inaccuracies. No mistakes.

Flotilla Admiral Assuntinella would inspect everything with uncompromising, firm eyes. Girls were mildly worried about this. The thin fabric by which her love stories were made was their first concern.

«How come the seam is puckered, right here? Why did you make this mess, eh?», Assuntinella would ask, her words sharp as needles.

A seam is supposed to be no heavier than the fabric itself. You are supposed not to even notice it. And the pattern printed on it has to be complete, perfect, unbroken, uninterrupted.

*

Verona, 2017.

«Mmh, it’s a bit tight here, on the hip», the woman with the Vuitton says.

«Oh, don’t you worry. Let me see…». The sales assistant puts her hands firmly on the dress. She looks pensive, almost musing. Then she touches the fabric and says: «Yes. That’s it. You see? Now that’s fine. It was just the way you wore it».

The customer is not that sure. Size forty, uh? Floral silky-ish Zara dress? More than one hundred euro… And a bit tight on the hip? «And, what about this sleeve? When I raise my arm the dress goes up, like this, you see?».

«Would you please put your arm down again, madame, and let me see?».

*

Solofra, 1952.

«Are they finally gone, girls? The boys? Stop it!».

«Are they finally gone, girls? The boys? Stop it!».

A sailor-tailor girl cannot use a wool thread to sew silk, cannot use light silk on an asymmetrical torso, without the help of some kapoc, which is a plant fibre used for padding.

She cannot make a bra that lets someone’s flesh pop out of the stretchy rim, especially under their bridal dress.

She cannot let the customer try to button her shirt if the button holes aren’t perfectly stitched.

She cannot let anyone wear a jacket whose lapels are sewn with uneven visible stitches.

When it came to fashion, my country was the country of «you must» and «you cannot».

There were no margins left for mistakes or laxity.

And every single body was a different world: silk suited someone, crêpe someone else, rough wool was perfect for that man…

One fabric, one shape, one colour: one woman.

*

Verona, 2017.

«To be honest, I would say that there is no flaw, here», the Zara clerk says. «This is the way the dress is supposed to breathe».

[…]

*

Solofra, 1952.

«Miss Troisi’s right leg is seven millimetres longer than her left», the Admiral said: «keep it well in mind! We don’t need to take any more measurements. We don’t need to trouble her again.’

«Miss Troisi’s right leg is seven millimetres longer than her left», the Admiral said: «keep it well in mind! We don’t need to take any more measurements. We don’t need to trouble her again.’

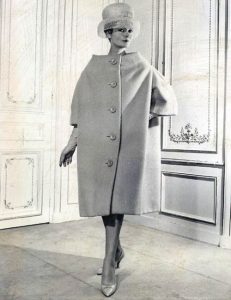

At the atelier, customers were offered a cup of strong coffee in silver pottery. Over the coffee table, Assuntinella took note of their preferences, their dreams; the woman they wanted to become thanks to her girls’ help. «So, tell me. What are you looking for?», she would ask them.

«Oh, I was thinking of a coat… It will be winter soon…».

«Well. What about cashmere?».

«Wouldn’t that be too expensive, Maestra?».

«Not necessarily, Miss Troisi».

«How much will I end up spending?».

«Let me do some maths…». She pondered over costs and other issues. «Six thousand lire?».

«That’s good», Miss Troisi said. And then, after a tiny hesitation: «Maestra, what if I pay for it in two tranches?».

«That’d be just fine. And now tell me: what colour are you thinking of?».

Then, the huge fabric sample book would be taken out. Glasses would be worn. Fingers would be eager to test the texture.

As for the shape, well, the Admiral would not permit anybody to get in the way of her scientific calculations.

«Will I be sure that absolutely no one else will have the same coat as I have, even in a different colour?».

«Please, madame. I know you don’t mean to offend. But, you know: we make exclusively bespoke pieces. You will be the only one in the world to have it».

«Not even a woman from Naples?».

«No».

«Or even Rome?».

«No one. I promise».

*

Verona, 2017.

«I think I’ll take it», the Vuitton woman says.

«I think I’ll take it», the Vuitton woman says.

«Perfect», says the clerk.

While she is putting the floral dress in a paper bag, the Vuitton woman looks out of the window.

The shoulder bag, the dress. The Prada pumps. She is so delighted.

I. Am. The. Perfect. Fit.

She feels she has achieved her right to be Someone.

She is absent-minded, lost in her own light happiness.

Otherwise she would see the Japanese girl shadowed by a white umbrella, and the American wife of some tycoon from Texas, wearing those awful boots; and the young Daddy’s girl with Ferragamo shoes, and the lady in her sixties.

Each of them wearing Zara. The floral dress.

And it was not even made by silk.

*

(And, please, now meet my mother Rosa)

(And, please, now meet my mother Rosa)

Scrittrice e giornalista, ho lavorato per oltre vent'anni nei quotidiani, dimettendomi in agosto 2012 da un contratto a tempo indeterminato.

Ho scritto il noir

Scrittrice e giornalista, ho lavorato per oltre vent'anni nei quotidiani, dimettendomi in agosto 2012 da un contratto a tempo indeterminato.

Ho scritto il noir

Recent Comments